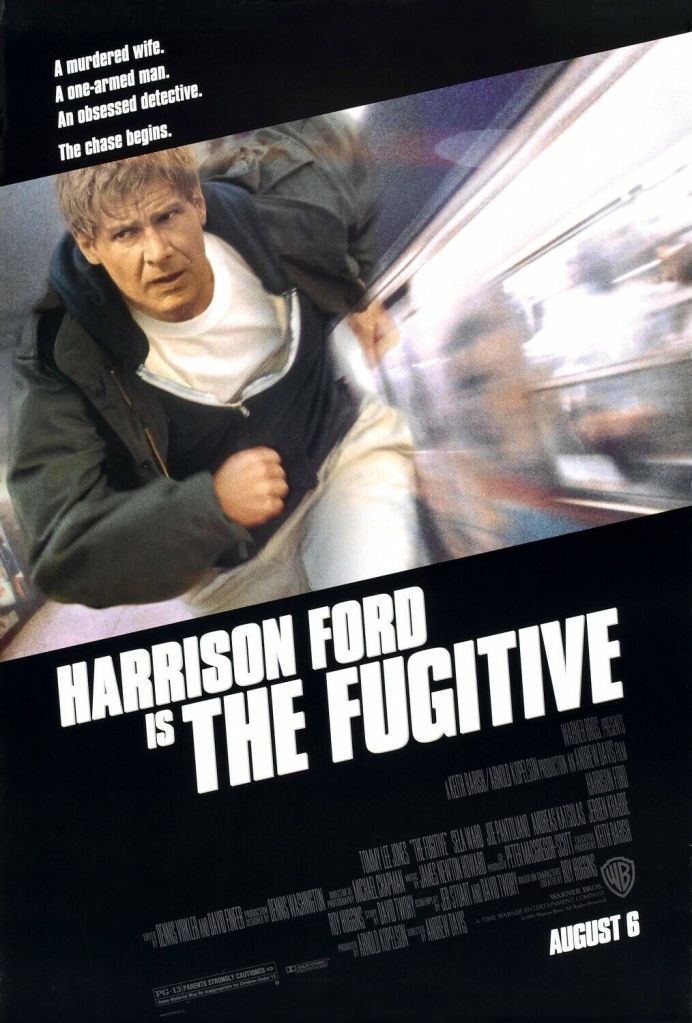

An innocent man goes on the run in the one of the finest thrillers of the 90s

Director: Andrew Davis

Cast: Harrison Ford (Dr Richard Kimble), Tommy Lee Jones (US Marshal Sam Gerard), Sela Ward (Helen Kimble), Joe Pantoliano (US Marshal Cosmo Renfro), Jereon Krabbé (Dr Charles Nichols),Andreas Katsulas (Fredrick Sykes), Daniel Roebuck (US Marshal Bobby Biggs), Tom Wood (US Marshal Noah Newman), L Scott Caldwell (US Marshall Erin Poole), Johny Lee Davenport (US Marshall Henry), Julianne Moore (Dr Anne Eastman), Ron Dean (Detective Kelly), Joseph Kosala (Detective Rosetti), Jane Lunch (Dr Kathy Wahlund)

I think there are few things more terrifying than being accused of something you didn’t do. How can you hope to prove your innocence, when no one listens and there isn’t a scrap of evidence to back up your story? How dreadful again if the crime you are accused of, that everyone thinks you are guilty of, is the brutal murder of your wife? The double blow of everyone thinking you guilty, while the real killer walks free. What would you do to clear your name? And how much harder would that be, if you were also on the run from the law who are eager to prep you for the electric chair?

It’s the key idea of The Fugitive, adapted from a hit 60s TV show, and undoubtedly one of the best thrillers of the 90s. Harrison Ford is Dr Richard Kimble, on death row for the murder of his wife Helen (Sela Ward). In transit to prison, an accident caused by a convict’s escape attempt gives him a chance to escape. Returning to Chicago, Kimble is determined to hunt down the mysterious one-armed man he knows murdered his wife and work out why. Problem is, he’s being chased down by a team of US Marshals led by the relentless Sam Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones), who’s not interested in Kimble’s guilt or innocence, only in catching him.

The Fugitive is propulsive, involving and almost stress-inducing in its edge-of-the-seat excitement. It’s a smart, humane and gripping thriller, both a chase movie and an excellent whodunnit conspiracy thriller. It’s one of those examples of Hollywood alchemy: a group of people coming together at the right time and delivering their best work. It’s comfortably the finest work of Andrew Davis, a journeyman action director, who delivers work of flawless intensity, perfectly judging every moment. It’s shot with an immediacy that throws us into the city of Chicago and its surroundings (Davis was a resident of the city and worked with photographer Michael Chapman to bring the real city to life on screen) and the film never lets up for a moment.

It gains hugely from the casting of the two leads. No actor can look as relatably harassed as Harrison Ford. Determined but vulnerable – there is a marvellous moment when Ford squirms with suppressed fear rising in an elevator filled with cops – Ford makes Kimble someone we immediately sympathise with. He’s smart – evading police, forging IDs, inveigling himself into hospitals to access amputee records – but constantly aware of the danger he’s in, brow furrowed with worry, narrow escapes met with near-tearful relief. Ford excels at making righteousness fury un-grating – the film makes a lot of his boy-scout decency – and never forgets Kimble is a humanitarian doctor, putting himself frequently at risk to save lives, from pulling a wounded guard from wreckage during his escape or saving a boy from a missed diagnosis in the hospital where he is working as a cleaner.

You need a heavyweight opposite him, which the film definitely has with Tommy Lee Jones. Jones won an Oscar for his hugely skilful performance. It would have been easy to play Gerard as an obsessed, fixated antagonist. Jones turns him into virtually a dual protagonist. Much as we want Kimble to stay one step ahead of the law, we respect and become bizarrely invested in Gerard’s hunt for him. Jones is charismatic as the focused Gerard, but also a man far more complex than he lets on. He genuinely cares for his team, takes full responsibility for their actions and finds himself becoming increasingly respectful of Kimble, even entertaining the idea of his innocence.

Not that an unspoken sympathy will stop him doing his job. When Kimble pleads his innocence at their first meeting his (iconic) response is “I don’t care”. Later, he doesn’t hesitate to fire three kill-shot bullets at Kimble when nearly capturing him in a government building – Kimble saved only by the bullet-proof glass between them. Jones never loses track of Gerard’s dedication above all to doing his job (the investigation he starts into Kimble’s case is motivated primarily by it being the most efficient way to work out where Kimble might go). But the edgy humour and pretend indifference hide a man passionate about justice and with a firm sense of right and wrong.

These two stars make such perfect foils for each other, it’s amazing to think they spend so little time opposite each other. Davis makes sure those few meetings have real impact, starting with their iconic early face-off at the top of a dam. A gripping chase through the bowels of this concrete monster, it’s also a brilliant establishing moment for how far both men will go: Gerard will continue the hunt, even after losing his gun to Kimble in a fall – because he has another concealed, ready to hand; Kimble won’t even think about using a gun and will go to the same never-ending lengths to preserve his chance at proving his innocence, by jumping off that dam.

The film implies they recognise these similarities in each other. Perhaps that’s why Kimble even eventually bizarrely trusts Gerard as a disinterested party – even while he remains terrified of Gerard catching up with him. The unpicking of (what turns out to be) the conspiracy behind Helen’s death is carefully outlined and surprisingly involving (considering it rotates around sketchily explained corporate shenanigans) – largely because Davis has so invested us in Kimble’s plight.

That’s the film’s greatest strength. Everything draws us into sharing Kimble’s sense of paranoia: that one misspoken word or bad turn could lead to his capture. Scored with lyrical intensity by James Newton Howard, it’s tightly edited and only gives us information when Kimble gets it. We only learn information about the night of the murder as he remembers or uncovers it. Davis twice pulls brilliant “wrong door” routines, where both editing and the careful delivery of information to us at the same time as Kimble makes us convinced that raids are focused on him, when they are in fact looking at someone else entirely.

This sort of stuff makes us nervous, worried for Kimble – and hugely entertained. I’ve seen The Fugitive countless times, and its relentless pace, constant sense of a never-ending chase and the brilliance of its lead performers never make it anything less than utterly engrossing. There is barely a foot wrong in its taut direction and editing and it’s crammed with set-pieces (the dam face-off, a chase through a St Patrick’s Day parade, a breathless fight on an elevated train) that never fail to deliver. It’s a humane but sweat-inducing thriller, a near perfect example of its genre.