Sirk’s melodrama packs in plenty of tight psychological observation among soap suds

Director: Douglas Sirk

Cast: Rock Hudson (Mitch Wayne), Lauren Bacall (Lucy Moore Hadley), Robert Stack (Kyle Hadley), Dorothy Malone (Marylee Hadley), Robert Keith (Jasper Hadley), Grant Williams (Biff Miley), Robert J. Wilke (Dan Willis), Edward Platt (Dr. Paul Cochrane), Harry Shannon (Hoak Wayne)

Money can’t buy you love. The oil-rich Hadleys live the high-life off the oil-empire built by patriarch Jasper Hadley (Robert Keith). Unfortunately, his children are both deeply unhappy and emotionally stunted. Kyle (Robert Stack) is an alcoholic playboy, Marylee (Dorothy Malone) a lonely woman who plays with other people’s lives to make herself feel better. Both are, in different ways, in love with sub-consciously resentful Mitch Wayne (Rock Hudson), the poor-boy childhood friend turned geologist who their father sees as the son he wishes he had. Mitch is in love with Lucy Moore (Lauren Bacall), an ambitious secretary at Hadley Oil – but Kyle also falls for her, marrying her. Marylee is in love with Mitch, who doesn’t feel the same. We already know from the film’s prologue all this is going to end with a bullet.

It makes for gorgeous entertainment in Douglas Sirk’s lusciously filmed melodrama, that helped lay out the template for the sort of soapy Dynasty-type TV monoliths that would follow years after. Sirk’s gift with this sort of material was to imbue it with just enough Tennessee Williams’ style psychological drama. Written on the Wind is awash with the glamour and beauty of wealth but, at the same time, demonstrates the immense psychological emptiness at the heart of the American Dream. What’s the point of all this luxury when those who have it are as deeply fucked up as the Hadleys are?

Their family is so wealthy the Texas town they live in is named after them and the run it like a private fiefdom, with the police running around like their errand boys. It’s not made them a jot happy. Both Maryann and Kyle are deeply aware of their own emptiness, rooted in the lack of attention (and love) from their father, a work-obsessed man who seems to have written his children off at an early age and invested far more time in training up Mitch like some sort of cuckoo-in-the-nest. Perhaps to try and win back their father’s love as much as to try and find meaning in their own, both of them want to possess Mitch: Maryann is destructively desperate to marry him, Kyle seems to want to become him and if one-way of doing that is by stealing the girl Mitch loves, all the better.

Wonderfully played by Robert Stack, overflowing with false confidence, jocularity and an utter, all-engulfing emptiness, Kyle talks endlessly about how Mitch is like a brother to him all while repeating as often as he can gently disparaging references to his poor-upbringing and dependence on the Hadley’s patronage. It’s coupled with his homoerotic (unspoken of course – it’s the fifties – but you can’t miss it!) obsession with Mitch. All of these confused, contradictory feelings wrap up in Stack’s (Oscar-nominated) performance, with the weak Kyle all too-readily believing Mitch might just be bedding his wife.

It’s an idea planted by Maryann, played with a scene-stealing bravado by Oscar-winner Dorothy Malone. Despite her vivacious energy and languidly casual confidence in establishing her pre-eminence over the newcomer Lucy, Maryann is a miserable, disappointed, deeply damaged soul, painfully bereft of any love and seeking meaning in casual couplings with a parade of gas attendants and hotel bellboys. Obsessively in love with Mitch, she dwells like Kyle on their childhood and the lost dreams of what might have been, but never was. This bubbles out over the course of Written on the Wind to an ever-more destructive Iago-like manipulation of the haplessly drunk Kyle, out of a mix of wanting everyone to be as miserable as she is and a desire to either own or destroy Mitch.

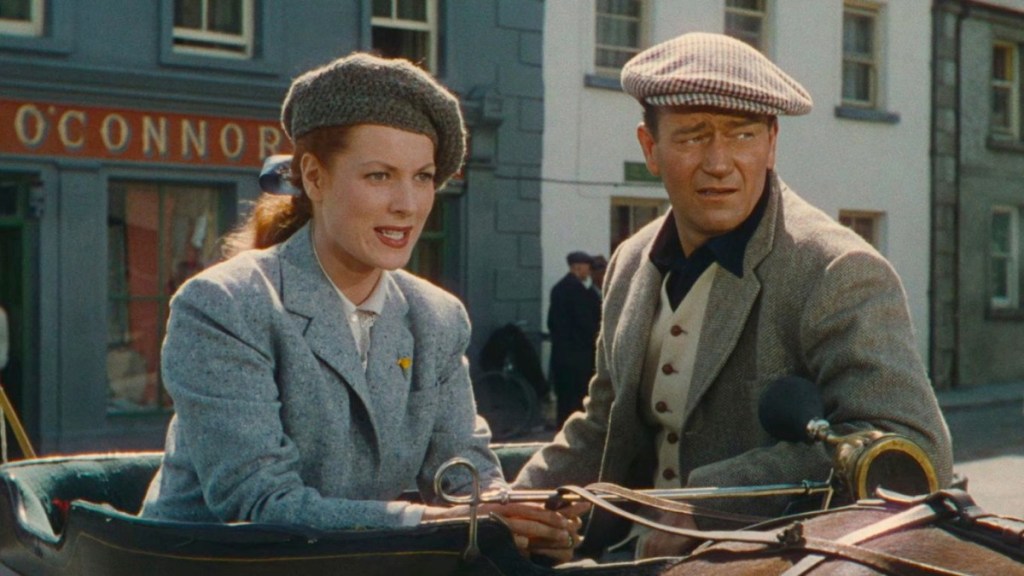

Malone and Stack triumph in these show-case roles, successfully building both frustration and sympathy in the audience. Opposite them, Hudson and Bacall (the stars!) play the more sensible, less interesting parts. Bacall’s strength and firmness balance rather nicely the contradictions in Lucy. A clear-eyed realist on meeting Kyle, attracted to the display of wealth while repulsed by his shallow, well-oiled, lothario routine, she never-the-less marries him, at least partly out of a desire to mother this fragile figure (she is genuinely moved by Kyle’s cockpit confessions of inadequacy and self-loathing while he flies her from New York to Miami for a date). From this Lucy confronts the psychological mess of the Hadley family with a stoic determination to make the best of things.

When does she start to develop feelings for Mitch? Mitch is clearly smitten on first sight, glancing fascinated at her legs while she stands behind a display board. But Sirk uses Rock Hudson’s similar stoic quality to great effect, turning Mitch into the epitome of duty, loyal enough to the Hadley family to bend over backwards to support the Kyle-Lucy marriage, all while clearly carrying an immense candle for Lucy. Saying that, part of the fun in Written on the Wind is wondering how much the patient Mitch is a conscious cuckoo, displaying all the intelligence, dedication and aptitude that Jasper so publicly lambasts his children for lacking (and whose fault is that?)

All these psychological soapy suds bubble superbly inside Sirk’s intricately constructed world. Every shot in Written on the Wind is perfectly constructed, splashes of primary colours dominating a world of pristine 50s class. Sirk frames the picture gorgeously, notably using mirrors effectively to place the characters in triangular patterns (Mitch at one point strikingly appearing in a mirror standing between Kyle and Lucy) or to suggest psychological truths (one shot angled to show Lucy brushing her hair in a mirror where we see a reflection of the reclining Maryann and don’t forget that marvellous closing shot of Dorothy subconsciously mirroring her father’s pose in the painting behind her while caressing a phallic model of an oil drill).

Sirk keeps events just the right side of melodramatic excess. A brilliantly staged sequence sees Maryann – dragged home from an assignation by the police – dance with a wild abandon in her bedroom while Jasper, horrified at realising how his disregard has warped Maryann, collapses to a heart-attack on the stairs. It’s a sequence that could be absurd but has just the right amount of reality to it, grounded as it is in Maryann’s self-loathing. Just as Kyle’s belief that impotence is going to consign him to being as much a failure in continuing the Hadley line as he is in everything else. Particularly since he’s constantly reminded of his inadequacy opposite the taller, smarter, better-at-everything Mitch who everyone else in the film openly seems to prefers to him.

It’s an extraordinary balance Sirk keeps, treating the characters with utter respect and affection while placing them in an over-the-top structure full of elaborate sets and overblown, melodramatic events and heightened feelings. Perhaps because Sirk never laughs at the concepts and content he’s created, we invest in both its truth and ridiculous entertainment quality. He does this while avoiding any touch of self-importance, never forgetting this is an old-fashioned melodrama. It makes Written on the Wind a hugely enjoyable, and surprisingly rich, character study mixed with plot-boiler.