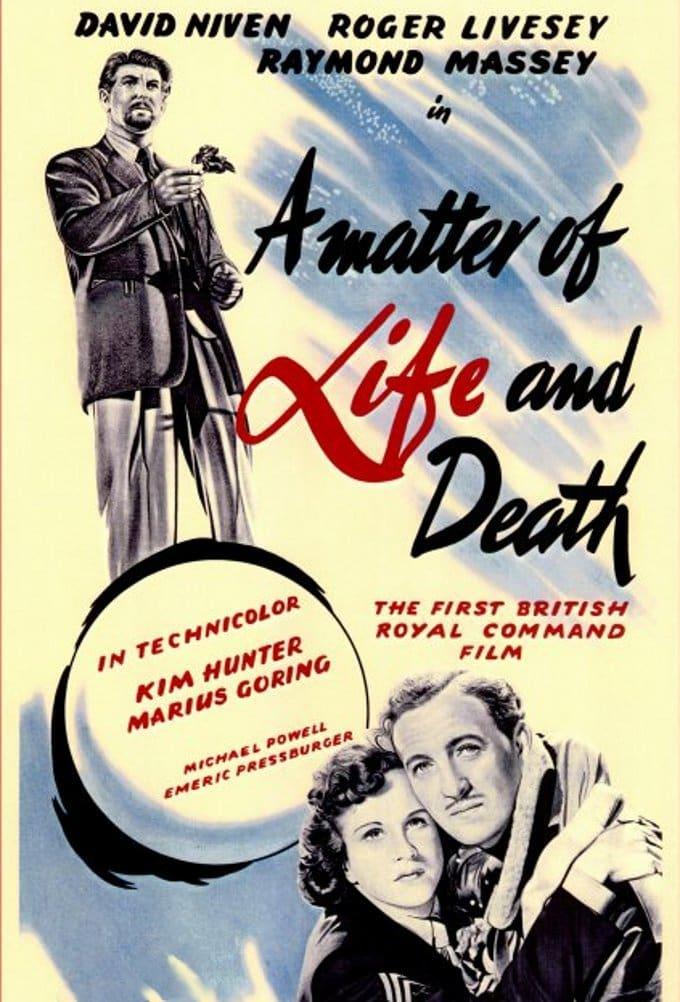

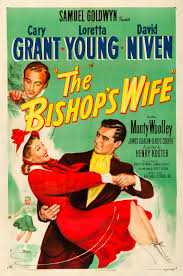

Charming Christmas enjoyment in this rather odd angel comedy that wins you over

Director: Henry Koster

Cast: Cary Grant (Dudley), Loretta Young (Julia Brougham), David Niven (Bishop Henry Brougham), Monty Woolley (Professor Wutheridge), James Gleason (Sylvester), Gladys Cooper (Mrs Agnes Hamilton), Elsa Lanchester (Matilda), Sara Haden (Mildred Cassaway), Karolyn Grimes (Debby Brougham)

Newly appointed Bishop Henry Brougham (David Niven) is forgetting who he is. Now spending all his time with the hoi-polloi (led by Gladys Cooper’s grande dame Mrs Hamilton) trying to secure funding for a new cathedral he’s rather lost sight of things at home with his devoted wife Julia (Loretta Young). Enter, seemingly in answer to his prayers, angel Dudley (Cary Grant). Taking up a role as Henry’s new assistant – with only Henry knowing the Heavenly background of his guest – Dudley sets about helping those around Henry rediscover their spiritual joy in life.

The Bishop’s Wife is a gentle, unassuming film, all taking place in the week before Christmas. It’s heart-warming, seasonal stuff, competently directed by Henry Koster, who efficiently juggles gentle character conflicts with a reassuring moral message. There are some rather charmingly done magical special effects sprinkled across the film: Dudley uses his angelic powers to instantly sort reference cards, fly decorations onto a chair, dictate to a self-operating typewriter and guide a snowball through the air with all the dexterity of Oliver Stone’s magic bullet. As a gentle piece of seasonal viewing, it gives you everything you could want.

Such is its easy charm and seasonal sweetness, it almost doesn’t matter that it’s quite an odd film. It’s no real surprise Dudley isn’t on Earth to help Henry secure mega-bucks he to build a grand cathedral (especially since principle doner Mrs Hamilton is more interested in making it a tribute to her late-husband rather God) but to help Henry work out his real focus should be the ordinary joes of his community and his marriage. That he should make sure he prioritises a humble choir at small local church St Sylvester’s and keep in touch with the parishioners he used to dedicate his time to. And, above all, that he should find time in his bustling calendar to keep the love in his marriage.

But the methods used by Dudley – away from angelic magic over inanimate objects and his ability to know everyone’s names before they even open their mouths and cross roads in bustling traffic without fear – are a little odd. Aside from shoring up a few people’s spiritual strength, he essentially begins a campaign of seduction, giving Julia the sort of loving attention Henry hasn’t given her in ages. It’s a slightly bizarre holy campaign – the angel who uses the temptations of the flesh to save a marriage – but it’s done with such innocence a viewer almost forgets the odd idea.

It also just about makes a virtue of casting of Cary Grant as Dudley. In a part that feels tailor-made for Bing Crosby, surely Cary Grant is no-one’s idea of an angel (a slightly abashed, heart-of-gold, demon perhaps). Grant, to be honest, slightly struggles with the role – at times the complete decency of Dudley leaves him rather stiff and the Grant twinkle gets one of its most subdued outings in cinematic history. However, Grant’s naughty charm does make us accept a little bit more that Dudley might just feel a little more than he’s saying with his attraction to Julia (even if, the rules of films, tell us there is zero chance of an angel being a seducer).

It still manages to get the goat of Niven’s Bishop, who increasingly resents this overly efficient new presence in his life more focused on charming his wife than getting on with what he presumes he’s there for – securing funds for the Cathedral. Niven (originally cast as the Angel – but his raffish charm would have been as unnatural a fit as Grant’s), does rather well as a decent man crushed under expectations and duty who has forgotten the things that really matter. Niven has a very neat line in quietly exasperated fury, so buttoned-up and English (despite being American!) he can’t give vent to his real feelings but hides it under genteel passive aggression. He also sells a neat joke that he is constantly rendered literally incapable of saying out loud that Dudley is an angel.

Loretta Young, between these two, has the least interesting part, trickly written. It goes without saying that a feel-good product of 1940s Hollywood is not going to have the wife of a Bishop actually, genuinely considering straying from her husband (just as, I suppose, it can only go so far in suggesting Grant’s Dudley is sorely tempted to leave his wings behind). Young’s role leans a little too much into the patient housewife, just eager for her husband to embrace day-to-day joys at home and not lose himself so much in work, but she manages to make it work.

These three lead a cast made up of experienced pros who know exactly how to pitch a fairly gentle comedy like this. Monty Woolley is great fun as a slightly over-the-hill professor, who needs to be befuddled by a never-emptying glass to stop him wondering why he doesn’t remember Dudley from the lectures he claims to have attended all those years ago. James Gleason offers cheeky, down-to-earth humour and sensibility as a friendly taxi-driver, while Gladys Cooper once again proves she can give austere grande dames more depth than anyone else in the business.

It all makes for a gentle, rather sweet and charming film despite that fact that almost nothing in it really make sense. In fact, it frequently falters as soon as you consider any of the plot at all or any of the actions and motivations of its characters. But then, this is basically a sort of Christmas Carol where the Angel arrives to re-focus the (not particularly imperilled) soul of one man, with wit, charm and warmth – and if it feels odd that also involves inspiring envy and jealousy (deadly sins right?!) in a Bishop, I suppose we should go with it. After all, it’s Christmas.