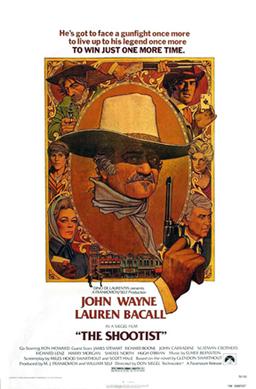

Wayne’s final elegiac Western as a dying gunslinger tries to go out on his own terms

Director: Don Siegel

Cast: John Wayne (JB Brooks), Lauren Bacall (Bond Rogers), Ron Howard (Gillom Rogers), James Stewart (Dr Hostetier), Richard Boone (Sweeney), John Carradine (Beckum), Scatman Crothers (Moses), Richard Lenz (Dobkins), Harry Morgan (Marshall Thibido), Sheree North (Serepta), Hugh O’Brian (Pulford)

It’s 22nd January 1901 and Queen Victoria has passed. Automobiles are starting to chug down roads, towns filled with electricity, telegraphs and trams, no longer look like the beat-up, dust-bowls the likes of Wyatt Earp policed. It’s a new age and the end of the Wild West. Which also means it’s the end of the gun-toting cowboys, like JB Brooks (John Wayne), who rode freely and grabbed their six-shooters faster than anyone else. Brooks rides into Carson City, his cancer terminal, his life lonely and full of enemies, wanting to live (and die) in his final week on his own terms.

You don’t need to be a psychologist to see more than a few parallels between Brooks and the man playing him, Hollywood legend John Wayne. Wayne himself was struggling with a cancer that claimed his life three years later and you could argue he too had outlived his time. The glory days of the Westerns were gone along with men like John Ford who built it. The Shootist draws huge piles of its elegiac emotion from this – with even more retrospectively added when it turned out to be the star’s swan song.

It’s strange to think Wayne wasn’t even first choice for the role (the producers were worried his health might not last), because he is so perfect for it that the line between Wayne and Brooks seems paper thin. Wayne still has the spark under the weakness of a sickly one who downs laudanum and relies on a cushion to sit comfortably. He’s a vulnerable man, raging quietly against the dying of the light. Lonely, devoid of friends whose entire life’s possessions are wrapped up in a saddle bag. But he’s also dangerous who can still be extraordinarily ruthless. He kills without hesitation when called on and resorts to violent threats (backed with a gun) when he needs to. But he needs to believe there is more to him than this.

Brooks is a man ‘scared of the dark’, quietly terrified about how he will be remembered. He sees himself as a ‘shootist’, a prowling man’s-man who shot when he needed to. What he doesn’t want to be seen as is a ruthless blood-soaked assassin dealing death left-right-and-centre. He humiliates a journalist (the weasily Richard Lenz) who wants a blood-and-guts killer’s story, sending him packing with a gun in his mouth. He turns away a funeral director (John Carradine, a lovely cameo) who offers a free funeral so he can sell tickets to see the dead killer. He’s desperate for some sort of positive legacy.

This overlaps with Wayne who, if he didn’t know this was his final film, surely knew it was probably his final Western. Siegel opens with a montage from Wayne films past (including Red River, Hondo and Rio Bravo) before crashing into a wide-screen, Fordian landscape that sees Wayne swiftly get the better of a would-be robber. Wayne’s performance is, whatever you think of him, undeniably heart-felt. His drawling pain-wracked face, full of fear and frustration, when told his fatal diagnosis by an old friend (an almost equally emotional cameo from that other drawling icon of the Western, James Stewart) is very moving.

You can see Brooks regrets when an old flame (Sheree North) arrives to suggest they marry – and the hurt when it becomes clear she only wants marriage so she can sell his story. The closest thing he has to a friend – Stewart’s doctor – he hasn’t seen for fifteen years (coincidentally the exact length of time since the two actors shot The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance). In fact it becomes clear the people in his life are enemies and rivals. From Richard Boone’s weasily rancher who blames Brooks for his brother’s death to Hugh O’Brian’s suave gambler who wants the chance to take down a legend. Even that’s better than Harry Morgan’s nervous Marshal, who bursts into relieved laughter when he hears cancer is going to take care of Brooks so he doesn’t have to.

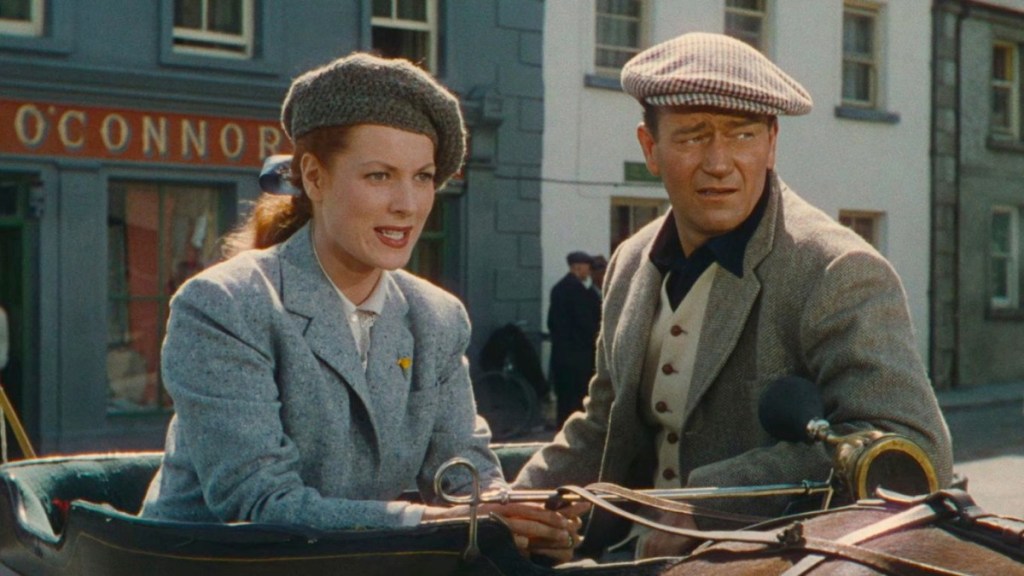

In his final week, Brooks finds some sort of connection not based on fear, envy or greed with Lauren Bacall’s (yet another golden-voiced legend) Bond Rogers, a widow with a tearaway son Gillom (Ron Howard), whose initial suspicion of Brooks soften. Bacall is excellent, full of humanity and sharp no-nonsense sincerity that hides a warmth you feel she’s had to crush down over years of holding hearth-and-home together. Brooks and Mrs Rogers form a quiet friendship, based on mutual loneliness, both actors playing beautifully in a series of quiet, sombre but gentle scenes, with Bacall drawing even more humanity from Wayne.

Mrs Rogers’ son, Gillom, becomes the embodiment of Brooks battle for a legacy. Ron Howard makes Gillom a cocky, immature dreamer, exactly the sort of guy who’d lap up the sort of blood-and-guts stories Brooks is worried his life will be turned into. He’s wowed when Brooks – alerted by his pain-ridden body keeping him awake – takes down two would-be assassins. But his mother is terrified that he could lead the wrong sort of life. And, eventually, Brooks himself starts to worry that all he’s doing spending time with him is leading Gillom towards an end like his: lonely and dying in a guest house, surrounded by strangers. It becomes the thematic struggle of the film, which is handled (like the rest) with an unlaboured patience.

It’s all building of course to Brooks deciding to go down on his own terms, clutching a gun not a laudanum bottle. The Shootist ends with a blood-soaked shoot-out that we all suspect its heading to, expertly assembled by Siegel. Siegel’s direction throughout is faultlessly smooth, avoiding all temptation to layer on sentimentality but instead let the sad tiredness of Wayne carry the emotion without loading the deck. It’s a beautifully done, quiet, restrained and perfectly elegiac picture that makes for a perfect final role for John Wayne. A sad, touching film about a strong-willed man fighting a last battle he can’t win, it’s a compelling watch.