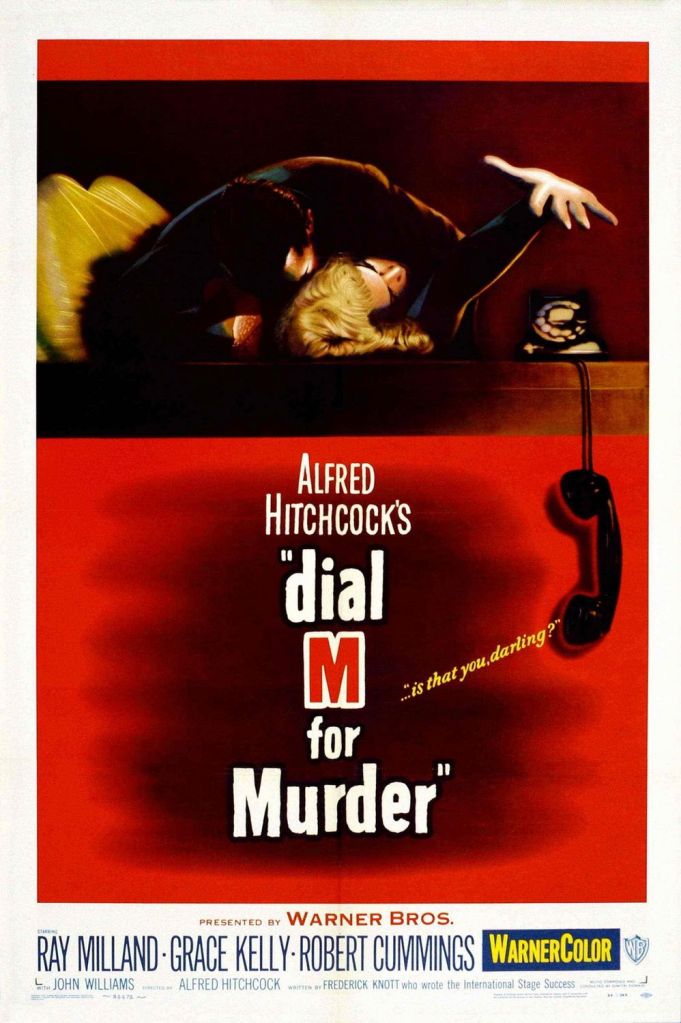

Second-tier Hitchcock thriller, with some interesting flourishes and entertaining moments

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Cast: Ray Milland (Tony Wendice), Grace Kelly (Margot Mary Wendice), Robert Cummings (Mark Halliday), John Williams (Chief Inspector Hubbard), Anthony Dawson (Charles Alexander Swann), Leo Britt (Party goer), Patrick Allen (Detective Pearson)

Tony Wendice (Ray Milland) is in a bind. A former tennis pro turned barely-successful sports goods seller, he loves the high life. Unfortunately, he’s running through cash like water – and, worst of all, most of it isn’t even really his but the property of his socialite wife Margot (Grace Kelly). And Margot is in the middle of an affair with trashy fiction writer, American Mark Halliday (Robert Cummings). An affair Tony knows all about, having stolen Margot’s love letters to anonymously blackmail her. But his new scheme is somewhat more permanent: blackmail disreputable Charles Swann (Anthony Dawson) into murdering Margot at a time when Tony has a perfect alibi. Sadly, things don’t go to plan – when do they ever? – and with Swann skewered in the back with a pair of scissors, Tony hurriedly improvises pining a pre-meditated murder charge on Margot all while avoiding the suspicions of Chief Inspector Hubbard (John Williams).

In his later extended interviews with Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock gave less than a few minutes to talking about Broadway-adaptation Dial M, describing it as, at best, a one-for-the-money assignment or sort of warm-up for Rear Window. He was similarly dismissive about the film being shot for 3D, which he described as a ‘nine-day wonder’ which he joined on the ninth day. Hitchcock had a tendency to play up to ideas of his genius, laying sniffy dismissal on what were viewed by critics as his lesser works (although Truffaut said Dial M grew on him every time he saw it). Actually, while Dial M does have the air of an assignment to it, there are some neat little Hitchcock touches it that, while not making it a classic, does make it an entertaining way to spend a Sunday afternoon.

After all, not many other directors would have so relished Swann’s body sliding down onto a small pair of scissors. Or found so many fascinating angles for shooting a (mostly) single-set, from lofted over-head shots that give Tony’s detailing to Swann of his elaborate plan a God-like force to crashingly tight close-ups on the phone Tony will use to dial in his alibi. Hitchcock also adds more than a little sexual energy to the play. There Margot’s affair is very much in the past, as opposed to here being very much keenly anticipated by Grace Kelly’s sensual stare over a newspaper to a clock counting down her assignation with Halliday. Hitchcock also avoided the sort of tedious ‘duck now!’ shots that has made 3D a joke in cinema-going circles, framing shots with a great deal of depth, placing key objects in different depths of field in the shot.

Dial M For Murder itself though, even with these little Hitchcock touches, tends to feel exactly like what it is: a well-heeled adaptation of a Broadway entertainment that is far more about plot, procedure and Christie-lite mystery than character or themes. (Actually, a mechanical operation like Dial M might well have appealed to Hollywood’s greatest ever proponent of the masterfully constructed tension piece more than her cared to admit). It’s a page-turner, Airport-novel transposed into glitzy, breezy entertainment where we get to flirt with someone completely naughty and wicked, but can be pretty sure the ‘howdunnit’ will become clear to everyone in the play, not just us (after all, the idea that Hitchcock – or anyone – will let Grace Kelly be executed for a crime she didn’t commit is of course preposterous).

Dial M plays very much into the Hitchcock playbook, where tension arises not from what we don’t know, but from the fact we know a little bit more than most of the characters. Just like Vertigo revealing its mystery surprisingly early, or watching a bomb tick down in Sabotage while its victims remain oblivious, we know from the start that this is all a scheme designed to entrap Margot. We know all the time exactly what Tony has done and the tension lies solely in working out whether Halliday or Inspector Hubbard will work it out and how they might manage to get Tony to pay for it. (There are also some echoes of Strangers in a Train, from Tony’s tennis-playing background to his sociopathic crime swop with Swann).

Tony is played with a suave, smugness by Ray Milland, which is just about likeable enough for a bit of you to want the selfish, shallow, self-obsessed Tony to get away with it. Milland won’t allow a slightly smug grin to disappear from his face – except in a burst of twitchy nerves when a stopped watch makes him concerned that he’s going to miss a vital phone call back home to establish his alibi during the attempted murder – and never once does he appear troubled by morality. In fact, he thinks rather sharply on his feet, pivoting in seconds from surprise at Margot’s survival to smoothly improvising a very convincing story, framed to (literally) hang Margot in. It’s an effective, enjoyable, pantomime-hissable performance which Milland has a lot of fun with.

He gets most of the film to himself, since Kelly is given a role that gives her little to do – although it does showcase her ability to communicate a great deal from looks alone, from her excitement at a future liaison, to growing fear as the police net draws around her. She’s certainly a far more magnetic performer than the bland Robert Cummings who has little about him to suggest he could set Grace Kelly all aflutter. The other key roles were filled out with actors from the original production: Anthony Dawson’s weasily opportunist Swann is perfectly convincing as the sort of cove who’d agree to murder to make his life easier while John Williams’ cements the image of the unflappable pipe-smoking detective who understands far more than it looks and lulls suspects into making fatal mistakes with an avuncular reassurance.

Dial M For Murder offers plenty of entertainment, even if it’s largely just a fairly routine plot-driven mechanical puzzle, spruced up by the odd inventive shot and engaging performance. But Hitchcock was probably right, that it sits very much in the second tier of his work.