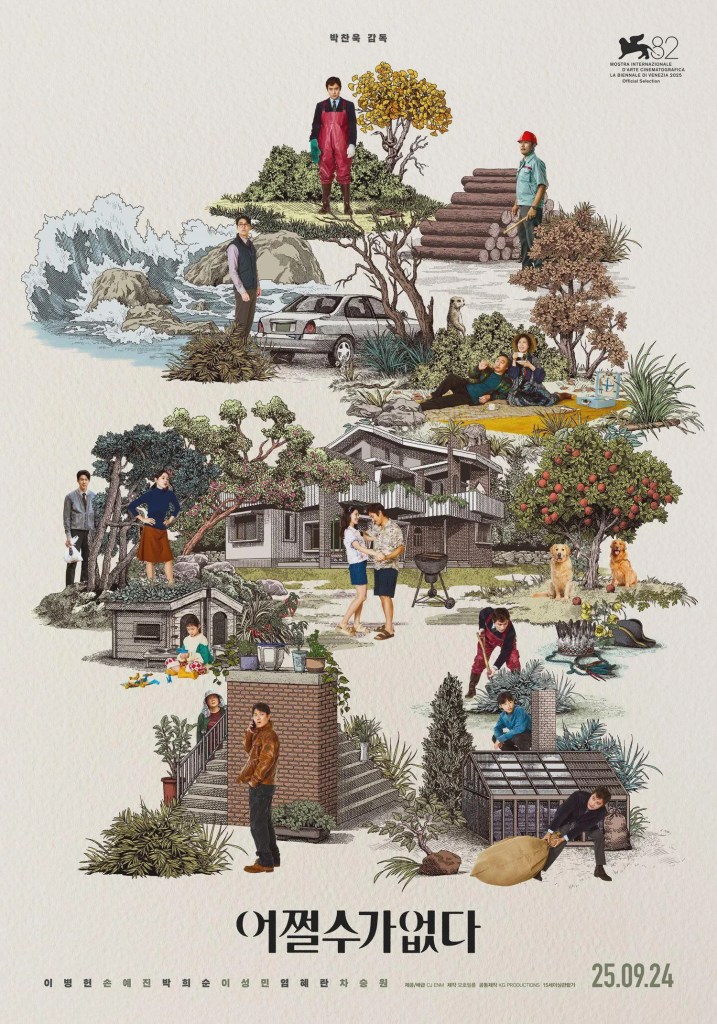

Jet black comedy, that makes strong, entertaining political points while testing our sympathies

Director: Park Chan-wook

Cast: Lee Byung-hun (Yoo Man-su), Son Ye-jin (Lee Mi-ri), Park Hee-soon (Choi Seon-chul), Lee Sung-min (Goo Beom-mo), Yeom Hye-ran (Lee A-ra), Cha Seung-won (Ko Si-jo), Yoo Yeon-seok (Oh Jin-ho)

Technology changes the world, sometimes so much it leaves people behind. That’s the starting point of Park Chan-wook’s dark (very dark!) comic drama, No Other Choice, which looks at the surreally bleak ends sudden unemployment in a changing labour market has on a regular joe who prides himself on being his family’s provider. It takes Parasite and mixes it with Kind Hearts and Coronets, but with the mood dyed jet black and a complex anti-hero who becomes darker the more we learn about him.

That anti-hero is Yoo Man-su (Lee Byung-hun), a hard-working paper industry supervisor, right up until his new employers follow-up a 25-year loyalty reward with a P45. Because who needs so humans when your factory can be run by a machine? Flash-forward a year later and Man-su is desperate: he can’t land a new job in the reduced paper industry and his wife Lee Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin) is suggesting it’s time to sell the home he spent a decade working to buy. Man-su decides on a desperate new plan: identify his more qualified rivals for a possible vacancy, murder them, then murder paper plant manager Choi Seon-chul (Park Hee-soon) and apply for his job. What could wrong?

This extreme response to feeling irrelevant in a changing world becomes the heart of Park Chan-wook’s black comedy, directed with his customary sharp-edged beauty with images and camera angles that make you want to swoon. It also walks a tight line between portraying Man-su as sympathetic, an (at first) laughably incompetent killer and, increasingly, a deeply flawed, bitterly resentful man, who resolutely refuses to adapt himself in any way to a changing world.

At first of course it’s hard not to feel sorry for Man-su, cast aside like a dirty off-cut from a company he has given his whole life too. No Other Choice takes its title from the cringe-worthy, rent-a-therapy mantra a jaw-droppingly shallow careers advisor pushes a roomful of redundant staff to repeat over and over again. It’s a mantra that stresses their lack of power and also bluntly sums up how they feel about their future: there are sod all real choices out there, only to adapt or die.

That’s certainly what Man-su, a hard-working supervisor respected by his staff, finds a year later. In a beautiful static shot of grinding irrelevance, a year flashes by of Man-su humiliatingly stacking shelves having failed time-and-time again at applications. A parade of humiliation follows: Man-su stripping out of his overalls in front of his unsympathetic (much younger) manager to attend an interview (shot in security camera distance long-shot); Man-su flunking an interview with clumsy answers to obvious questions, squinting at his interviewers sitting in front of a sun-bathed window; the smug father of his adopted son’s best friend offering to buy a house Man-su has poured his heart and soul into, while constantly disparaging it; literally begging outside a bathroom for Seon-chul to read his CV….

Is it any wonder he is overcome with something between resentment and despair? All that hard-earned respect, years of experience and mastery of the intricate details of paper production means nothing. All those promises of working hard and getting your due reward exposed as a puff of bullshit.

Maybe murder is a fair way to deal with this. After all, it’s not really his choice, right? Advertising a job vacancy at a fake company, he collects his rival’s CVs and carefully selects the better qualified to remove them from the jobs market. He then embarks on a life of crime which Park depicts with a haphazard chaos. Man-su is no expert: he needs multiple attempts to even take a pop at his first target, leaves key evidence behind at crime scenes (only chance saves from arrest) and makes a mess of hiding his tracks.

Lee Byung-hun has a gloriously disbelieving look to him, constantly unable to fully process what’s happening to him. Instead, he’s trying desperately to keep up a front that slowly collapses. It’s a brilliant performance, one that keeps us liking Man-su, even as his previously well-hidden dark side bubbles to the surface. Man-su prides himself as a careful, methodical gardener and he applies the same to his family, who he wants to protect and nurture. Each murder sees him crush more and more of this quality in himself: the man who tries to shelter his first victim from his wife’s infidelity, later finds himself comfortable dispatching others with cold-faced, determined ruthlessness.

It’s part of what makes No Other Choice such a genuinely surprising film. It would have been very easy for Park to embrace the dark comedy of Man-su’s Kind Hearts removal of obstacles. You could well imagine a Hitchcockian black comedy version. But what Park does is make us question our sympathies with Man-su. Pride is shown as his major flaw. Despite a multitude of transferable skills, he never considers new careers (something he even berates one of his targets for not doing, a rant clearly aimed as much at himself). He refuses free treatment for his tooth infection from Mi-ri’s charming dentist boss. He doesn’t attempt to change his lifestyle – or outgoings – during unemployment, burning through his redundancy package. He can’t imagine anything other than stepping back into an identical position to the one he has left.

On top of this, he’s an insecure, fragile man. A recovering alcoholic, Mi-ri makes clear when on the booze he was short-tempered, even striking their son. He becomes consumed with jealousy at her friendship with her boss (even, pathetically, asking to smell her underwear to check she has remained faithful). He’s very aware of his poor background and limited academic achievements. It becomes clear his job had grown to define him as a man of worth: without it he’s terrified that he is nothing, for all Mi-ri makes clear she doesn’t feel like this (much like the wife of his first victim makes clear its not her husband’s unemployment that’s the problem, more his drunken, self-destructive, self-pity).

Park doesn’t make it easy with Man-su’s victims. These aren’t comic portraits, but deeply human figures, both of whom are eerie self-reflections of Man-su. Goo Beuom is a tragically self-pitying alcoholic. Ko Si-jo is a devoted father of a young daughter, working over time to try and provide his family. These aren’t comic caricatures we can enjoy watching get bumped off (like multiple Alec Guinnesses) but living-breathing people, touched by tragedy. That’s why Man-su can barely bring himself to look at them when the moment comes.

It’s a darkness that starts running more and more through No Other Choice as Man-su’s determination to regain his status starts to destroy the very things he claims to value most: his family, principles and peace of mind. No Other Choice is fiercely critical of a world of AI-powered industrialisation where human workers are irrelevant: but Chan-wook refuses to romanticise the bitter realities of the people left enraged and resentful at the impact on their lives. It makes for an uncomfortable and challenging comedy, full of moral quandaries and sharp political statements.