Dreyer’s searing, close-up dominated, silent masterpiece is a truly unique piece of cinema – and still astounding

Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer

Cast: Renée Jeanne Falconetti (Joan of Arc), Eugène Silvain (Bishop Pierre Cauchon), André Berley (Jean d’Estivet, prosecutor), Maurice Schutz (Canon Nicholas Loyseleur), Antonin Artaud (Bishop Jean Massieu), Gilbert Dalleu (Jean Lamaitre, Vice-Inquisitor), Jean d’Yd (Nicholas de Houppeville), Louis Ravert (Jean Beaupère), Camile Bardou (Lord Warwick)

It falls to few films to have the grace to redefine what cinema could do. Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc is one of those films that simply demands to be seen – and once seen will haunt you forever. For a film in many ways so profoundly simple, it is also profoundly wise, deeply affecting, troubling, moving and finally almost unbearably painful. Shot in an iconic collection of interrogative close-ups, Dreyer’s masterpiece earns its place as one of the greatest films ever made.

Dreyer’s masterstroke here was not to create a conventional biopic. We see nothing at all of Joan’s finding of her faith, her campaign against the English or exploits on the battlefield. Instead, we witness only the final days of her life, pulled up as a heretic before a biased and arrogantly superior ecclesiastical court. We first see her not as a strong figure (or even defiant) but a frightened girl creeping into frame, dwarfed by spears and towered over by a priest. If the French producers were expecting a triumphant eulogy to their recently beautified national saint, they had a shock.

Mind you, they had plenty of shocks already. Dreyer’s film used one of the most expensive sets ever built. Seven million francs were shelled out on an intricate medieval castle and courtyard, full of interconnecting passage ways. Dreyer’s surviving model of the set is impressive. You have to assume the real thing looked impressive as well, because the film almost never shows it. The Passion of Joan of Arc takes place in tight, fixed, searching close-ups – most strikingly of Joan but also of her interrogators and the witnesses of her martyrdom. The epic is pulled down to the tightest and most intimate framing of all: the human face, with all its blemishes, imperfections and dizzying emotions.

Those emotions play most sharply across the face of Renée Jeanne Falconetti. Falconetti had performed briefly in one film eleven years previously, but this was effectively her only work on camera. And it is extraordinary, one of the most searing, memorable performances in the history of cinema. You will never forget the fixed glare of her eyes, the devotional joy in her face and the self-accusatory pain in those same eyes when she briefly recants. Dreyer and Falconetti worked closely together to chart every single moment of the complex array of emotions.

Hope, despair, defiance, fear, self-loathing, determination, shrewdness, timidity – all these expressions form both in micro and in carefully held shots that allow Falconetti to naturally move from one to another. This is one of the few films that really has the patience to record thinking. We see realisations dawn upon her, her face slowly changing to process them and then (frequently) her eyes filling with genuine, heart-rending emotion. It becomes an intense – painful – study in powerlessness and vulnerability, dappled with little moments of hope. Her joyful face when the shadow of a window forms a cross on the floor is almost unbearable.

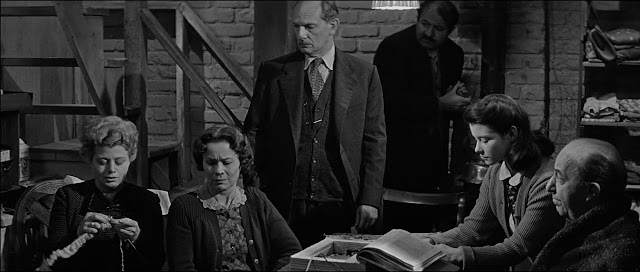

Not least, because as she stares enraptured at this shadow, we cut back and forth to her interrogators forging a letter from the Dauphin to further break her spirit. Dreyer introduces the priestly interrogators with one of the few motion shots, a long tracking shot panning across the rows and rows of well-fed, comfortable men who are about to stand trial over this young woman. The close-ups reveal as much about the priests as it does Joan. A complacent, arrogant Bishop smirks while he picks his ear. Others snigger and stare in disgust at this abomination.

But Dreyer’s film is remarkable for how much scope he gives many of the priests. We see some of them begin to form serious doubts as Joan’s sincerity flies in the face of their expectations. Schutz’s Canon – writer of that fake letter – doubts grow, finally seen sadly turning away as she is prepared for burning. Even Silvain’s Pierre Cauchon isn’t a sadist, or really a bully – just someone who can’t imagine a world in which he is wrong. It’s what leads him to push and push, sometimes with a resigned unease, willing Joan to recant. Some burn her sadly: but burn her none-the-less.

Dreyer’s film though is a passion – and, like the medieval plays that inspire it, it wants to take us on a journey to understand the power of Joan’s faith and nobility of her martyrdom. The priests convey us and Joan to the torture chamber – one of the few wide shots Dreyer uses, to show us the extent of the ghastly devices. A giant breaking wheel is turned with increasing, horrifying speed, its many spikes blurring, as Cauchon demands Joan recant. It drives her into a fainting fit and she is bled. A real AD gave up his vein to produce shockingly, horrifyingly genuine spurts of blood.

Dreyer’s claustrophobic close-ups are not designed to throw us into Joan’s POV, but to make us feel as trapped as she does. It’s striking that many of the close-ups can’t be either Joan’s perspective or the priests. There isn’t always continuity between them – we’ll cut from a full-on view, to a side-on one, a camera angle above and then below, staring up or glaring down. The effect is less about putting us into the eyes of its characters, than to make us feel like a spirit in the room, powerless to intercede. There are no establishing shots for geography, only the onslaught of faces shouting at the camera or starring with confessional pain at the lens.

Which helps even more with the sense of devotional mystery play Dreyer is aiming to create, using the language of cinema in ways no theatre-maker ever could. As Joan is mocked, and garlanded with a false crown, by braying English soldiers, we feel as trapped as she does. When her hair is sliced away, the shears feel uncomfortably close, but just as traumatising is the agony of guilt on Falconetti’s face, at the realisation she has turned her back on her God.

It’s been said watching the film is like watching, as if by a miracle, actual documentary footage of the trial. This realism is one of Dreyer’s master-strokes. So many other directors would have allowed touches of medieval pageantry, of poetry among the stark images. The closest we get to this is a doubtful Joan starring at freshly dug up skull, from the eye socket of which wiggles a worm, while deciding whether to confess. Other than that, the lavishness (that perhaps the producers expected) is nowhere to be seen, helping make the film as punishing and (finally) moving to watch as it is.

The final burning offers no release. The camera maintains its focus on Joan, who quietly passes the rope to her executioner so he can bind her to the stake, then turns her eyes one final time to heaven before her face is obscured in smoke and flames. Dreyer’s camera doesn’t flinch, and its fair to say Joan’s death is as horrifying as anything caught on screen. An alarmingly life-like body blackens, burns and shrivels in uncomfortable mid-shot. In a stunning swinging camera shot, soldiers prepare weapons to disperse the crowd. Dreyer’s camera doesn’t shy away from this atrocity either: bodies are battered, a fallen woman stares sightlessly in the camera, screaming mothers run with children in their arms, a cannon pans across the camera and fires into the crowd. The smoke of the burning – to which we constantly cut back to – fills the screen. It’s bleak and hellish.

This is truly a passion, a sense of the ascension of the spirit through the dread of pain and suffering. And we feel every moment of it through the uncomfortable but profoundly moving immersiveness of Dreyer’s camera – and the breathtaking camerawork of Rudolph Maté – and the astonishing raw performance of Falconetti. The Passion of Joan of Arc sears itself onto your memory, a visceral, unique piece of film-making unparalleled in the history of the medium.