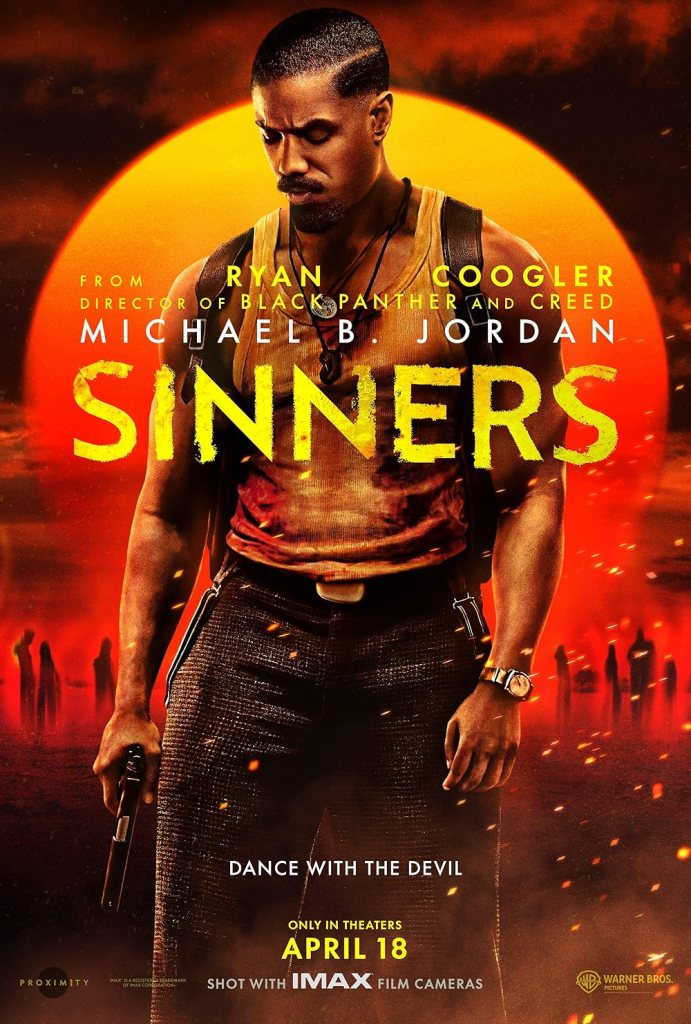

Del Toro’s dream project makes it to the screen in a lavish gothic spectacular

Director: Guillermo del Toro

Cast: Oscar Isaac (Baron Victor Frankenstein), Jacob Elordi (The Creature), Mia Goth (Elizabeth Harlander), Felix Kammerer (William Frankenstein), Lars Mikkelsen (Captain Anderson), Christoph Waltz (Henrich Harlander), David Bradley (Blind Man), Charles Dance (Baron Leopold Frankenstein), Ralph Ineson (Professor Krempe)

When he was a kid del Toro fell in love with James Whale’s Frankenstein. It was his dream project to create his own version of Mary Shelley’s classic. Year of dreaming pay off in this visually gorgeous, and emotionally engaging film – even if it’s also a little overlong and overindulgent. Del Toro throws everything into Frankenstein, creating a grand Gothic epic whose sympathies firmly lie with the abused Creature.

You must be familiar with the plot: in eighteenth century Germany, Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac), driven by never-really-resolved anger over his mother’s death, dreams of conquering death. With the funding of arms dealer Harlander (Christoph Waltz), who is also uncle to the woman he loves: Elizabeth (Mia Goth) who happens to be fiancée to his younger brother William (Felix Kammerer). On a stormy night, he gives life to the Creature (Jacob Elordi) but quickly rejects him. The Creature tries to find a place in the world, only to discover the world is full of prejudice and violence towards him and the Creature’s resentment against his thoughtless creator grows.

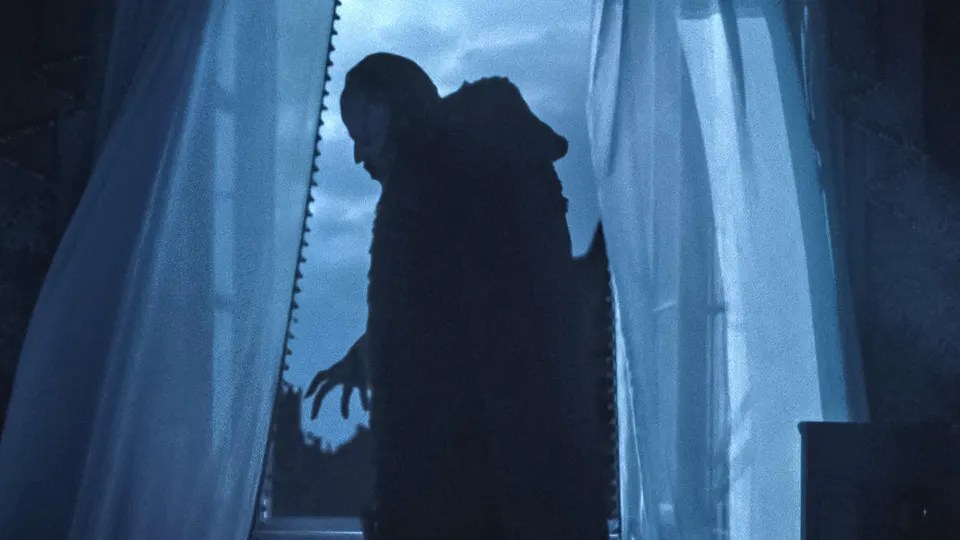

Del Toro’s film looks absolutely stunning, a sumptuously designed Gothic melodrama with extraordinary sets, grand costumes and beautiful cinematography (the Polar-set framing device is particularly striking, covered in lusciously contrasting blues and greens). There are striking echoes of the visual intensity of Pan’s Labyrinth, with Frankenstein’s lab turned into a mix of laboratory and classic temple, including a giant Medusa sculpture. The birthing sequence is a grandiose, operatically Gothic thing of beauty, a version of Whale’s film dialled gloriously up to eleven.

Del Toro’s film goes back to the novel in some ways (in themes and its Polar framing device), but in many ways it’s more of a complex, emotional reimagining of Whale’s film. Isaac’s Frankenstein, an egotist in need of an audience feels very similar to Colin Clive. Whale’s key motif, the Creature’s romantic yearning for the sun, becomes thematically central here. As there, Frankenstein conducts his experiments in a colossal Gothic tower, keeps the Creature chained and makes vague attempts to rear it and takes no responsibility for his actions or the deaths connected to it (in fact Isaacs’s Frankenstein lies and lies in a weasily attempt to protect his reputation). Waltz’s arms dealer funder of Frankenstein’s insanity feels like a version of Pretorious from Bride of Frankenstein, while del Toro goes even further than that film in deepening the bond between the Creature and the Blind Man.

Del Toro also doubles down on Whale’s implicit sympathy for the Creature. Here re-imagined as possessing near super-human strength and durability (his violent responses to being attacked being partially a result of his own strength being uncontrollably great), his child-like vulnerability is as dialled up as his actual physical invulnerability. The Creature feels, first and foremost, like a thought experiment by Frankenstein – and the fact this experiment has effectively rendered the Creature immortal and capable of a Wolverine-like cellular regeneration, condemned to walk the Earth forever alone only heightens the creator’s myopic selfishness.

One of del Toro’s key themes is terrible parenting. Much as he loathed his domineering, brutal father (Charles Dance, in a role perfectly crafted for his austere distance) who caned his face (his hands are too precious) when he flunked remembering anatomy facts, Frankenstein ends up echoing his father’s approach. When the creature constantly fails to say anything other than ‘Victor’, he too reaches for a cane to beat learning into him. Like his father, he resents the creature for being a bad reflection on him. He is, effectively, a dead-beat Dad, casually fathering a child which he has no idea how to treat, who falls back on cruelty.

There can be few Frankenstein’s on film less sympathetic than the version played here by an impressively egotistical Oscar Isaac. He’s full of preening self-importance and self-justification, obsessed with his task but giving no thought to its consequences. Twice he reanimates corpses then callously switches them off without a second thought. Giving birth to Frankenstein – just like in Whale’s film – after an initial interest (that is really self-congratulatory pride) his reaction is to chain him up in the basement and lose patience at him. With his constant milk-drinking there is a sense he’s a little boy who never grew up, and to him love is founded on possession: first of his mother, then his brother, then Elizabeth, all of whom at various points he wants to keep to himself – while his anger at the Creature is rooted in his failing to meet Victor’s expectations.

Frankenstein is at heart an angry mother’s boy, resenting his father for ‘taking’ his mother away from him (del Toro even has him wrapped in his mother’s distinctive red when he wakes to discover the Creature lives). There is more than an echo in that in his love for Elizabeth, the fiancée of his younger brother (who he also subconsciously resents for both ‘killing’ his mother in childbirth and for having the sort of relationship with his father Victor never had). These Freudian feelings are subtly enforced by Mia Goth playing both roles (it’s so subtly done I missed it first time round). Victor’s love for Elizabeth is just as possessive and selfish as that for his mother – and in the same ways his contempt for the Creature is for ‘failing’ him.

By contrast with this monster, the Creature is presented overwhelmingly sympathetically. Played with an outstanding physical and emotional commitment by Jacobi Elordi, he’s framed as a child stumbling towards a painful adolescence. Freshly born, he waddles like a toddler, stares in fascination at leaves floating on a stream and painfully forms the word ‘Victor’. Of course, it never occurs to his creator that this is the equivalent of “mama”. Only Elizabeth, who feels an immediate affinity with the sensitive soul, understands this. Only she tries to speak to him – or asks what his name is.

The poor Creature escapes into a world he quickly full of senseless, prejudiced violence. He bonds with a stag – only for the creature to be shot in front of him by hunters (who instantly turn their guns onto him). In conversation, Elordi presents a man who is sensitive, kind and gentle but capable of anger and fury. Del Toro crafts a tender relationship between the Creature and David Bradley’s Blind Man (the only person, other than Elizabeth, to look past his appearance). The film’s second act, focusing on the Creature’s emotionally painful interaction with the world is its strongest – not least because you feel throughout del Toro’s deep bond with him.

After all this, it’s surprising that Frankenstein ends on a note of hope. Del Toro’s film isn’t always quite nimble enough for this: some of its more optimistic moments can feel as if they have emerged a little thin air (or from the optimistic wishes of the director). In particular, Elizabeth’s bond with the Creature feels so swiftly sketched out it failed to completely convince (more time on this and less time on Waltz’ creepy arms dealer would have been welcome). But this feels like a passionate, committed and perhaps above all beautiful to-look-at piece of work with a real emotional heart. This easily lifts it into the upper echelons of Frankenstein adaptations.