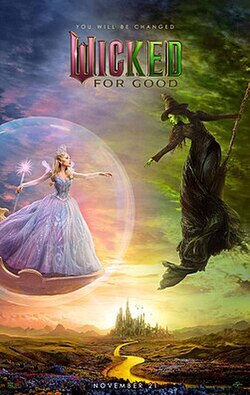

Part 2 doesn’t match Part 1 for entertainment or depth, but has enough moments to work

Director: Jon M. Chu

Cast: Cynthia Erivo (Elphaba Thropp), Ariana Grande-Butera (Glinda Upland), Jonathan Bailey (Fiyero Tigelaar), Michelle Yeoh (Madame Morrible), Jeff Goldblum (The Wizard of Oz), Ethan Slater (Boq Woodsman), Marissa Bode (Nessarose Thropp), Bowen Yang (Pfannee), Bronwyn James (ShenShen), Colman Domingo (Cowardly Lion)

Act Two comes to the screen in Wicked: For Good, putting the finishing touches to a five-hour journey through a single stage musical. While there are literally hundreds of millions of reasons for splitting the film in two, you can’t doubt the passion and love for the source material from everyone involved. However, Wicked: For Good, while shorter than the first film, feels longer: more padded but also more aimless, exposing more of the flaws of the musical less apparent when Act Two breezes past in about an hour. It’s still an entertaining watch, but it lacks the explosive, glorious impact of the first film.

Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) has been firmly branded public enemy number one as the Wicked Witch of the West. Meanwhile, her old friend Glinda (Ariana Grande-Butera) is the universally beloved face of the regime, showmanship and trickery hiding her complete lack of magic. Elphaba is fighting a losing battle for hearts and minds, failint at her attempts to expose the Wizard’s (Jeff Goldblum) lies and to protect the animals of Oz from persecution. Attempts at good deeds constantly go wrong and the arrival of a young girl from Kansas brings chaos. Will Elphaba and Glinda heal their relationship and will Oz be saved?

Wicked: For Good suffers for covering the weaker second act. Most of the best songs were in the first film. The first act also has more interplay between the two leads (whose relationship is the heart of the story) and had a clearer coming-of-age arc with Elphaba’s eyes being opened to the nature of Oz. Wicked: For Good tries to tackle an awful lot (Good and Evil! Animal rights! The Wizard’s oppression and guilt! Propaganda and manipulation! Backstory for every character in The Wizard of Oz! Elphaba and Glinda’s relationships with Fiyero!) But it often ends up under-cooking, hand-waving and fudging many of them. It chops and changes its focus so often, that developments seem sudden or under-explained.

This is where the extended run-time doesn’t help. The logic leaps that can be done in a few minutes of dialogue between songs in an hour of stage-time, make less sense when stretched over two hours plus. One of Elphaba’s main motivations is protecting the animal’s rights, with these creatures literally losing their voice. Despite opening with her trying to free slave-worker animals from building the Yellow Brick Road, eventually this plot-line feels lost in the shuffle. The motivations and mechanisms of the persecution are unclear, and then confusingly bunched in with racist laws against Munchkins. Similarly, Jeff Goldblum’s Wizard switches from a sociopathic arch-manipulator, into a drink-dependent man coated in guilt, without this journey being amply explained.

Wicked: For Good also awkwardly shoe-horns in events from The Wizard of Oz (there is a lot of Dorothy and her companions on the margins) and comes up with not-always-well-developed reasons why Elphaba and Glinda do the things-they-do as required by Wizard of Oz, without contradicting the more complex, interesting characters they are here. Again, these are flaws revealed by the extended run-time which gives more depth to the leads, but little of its added hour to giving more depth and context to the plot and themes the film is trying to handle, making them feel under-powered.

That’s not to say there are not plenty of positives. Wicked: For Good really understands its core strength is the relationship between its leads, and the chemistry between Erivo and Grande is still dynamite. It’s made very clear they are taking opposite approaches in interpreting ‘what’s best for Oz’ (for Elphaba it’s ending the lies, for Glinda it’s keeping people happy – very on brand for both). Their scenes are the film’s emotional heart, whether laughing or crying together, or even (in one laugh-out-loud moment) literally fighting. Just as in the first film, Wicked: For Good demonstrates the different perception an outsider and an insider brings to a situation and how this informs their loyalties and actions.

Erivo’s wonderfully draws on deep loneliness and growing frustration at her inability to change things, capturing the sense of someone certain she’s in the wrong, but who utterly lacks the ability to persuade (be that animals to stay and fight, or Ozians to take another look at the Wizard). Her deep need for friendship (and romance with Jonathan Bailey’s effortlessly charismatic Fiyero – rather short-changed by screen time here) is clear, even if her transition to embracing elements of ‘the villain’ seems rather forced. Her singing remains breathtakingly good with ‘No Good Deed’ an extraordinary show-stopper.

However, the film might just belong to Ariana Grande. If Wicked was Elphaba’s coming-of-age, this is Glinda’s. Grande brilliantly shows how fragile the bubble of happiness Glinda has built is. Glinda’s realisation that from an early age (an excellent childhood flashback scene helps here) she hid her feelings with an immaculate smile is very well explored – as is her realisation that she is universally beloved, but has no real friends. Grande finds a desperation, fragility and sense of pain that only just peak out – feelings covered well in the best of the film’s two new songs ‘The Girl in the Bubble’, with Chu using reflections to stress Glinda’s realisation of the lies she has told herself.

Of the many themes the film tries to cover in a broad sweep, this one comes out best while others fall by the wayside. Propaganda and dictatorship in Oz sort of sits there as a presence without getting real focus. The oppression of the animals (and imagery of them working in whips and chains) makes a big emotional swing the film isn’t willing to commit to. The other new song, ‘No Place Like Home’, is an unforgettable ballad that awkwardly stages Elphaba begging animal users of an Underground Railroad to stay and hope for the best (imagine telling that to real-life Railroad users). There are darker elements I liked (Marissa Boda’s Nessarose and Ethan Slater’s Boq explore jealousy, possessiveness and rage in a surprisingly daring way, told with an effective economy I wish Chu could have found more often).

When Wicked: For Good works, it works. The impressive visual design from the first film is still in place. Chu directs with energy and vibrancy and gets real emotion from the moments between the leads. But I miss the large choreographed numbers here (perhaps expected from a darker Act Two) and its plot is often unfocused, forced and manages to use double the time to barely extend (or make more interesting) the level of thematic exploration the original musical does. I didn’t enjoy it as much as the first one and becomes a little too trapped by fitting into Wizard of Oz but it’s still an entertaining ride.