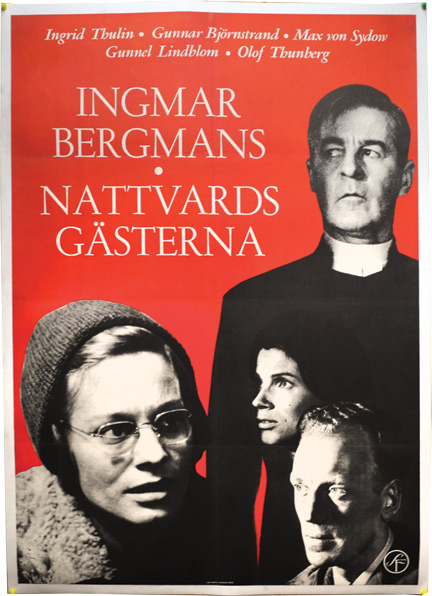

Faith is thoughtfully questioned in Ingmar Bergman’s spare, bleak and striking masterpiece

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Cast: Gunnar Björnstrand (Pastor Tomas Ericsson), Ingrid Thulin (Märta Lundberg), Gunnel Lindblom (Karin Persson), Max von Sydow (Jonas Persson), Allan Edwall (Algot Frövik), Kolbjörn Knudsen (Knut Aronsson), Olof Thunberg (Fredrik Blom), Elsa Ebbesen (Magdalena Ledfors)

It would surprise many to hear Bergman held Winter Light in the highest regard among his films. An austere chamber piece, largely set in a cold, naturally lit church, it’s the middle chapter of his thematic trilogy on faith and it serves to correct any sense of hope left remaining from in Through a Glass Darkly. Winter Light – with its lead character a semi-biographical combination of Bergman’s father (himself a Lutheran Pastor) and Bergman himself – begins with a robotic preaching in a Church and ends firing up another such sermon to an empty Church. This is a world where, if there ever was a God, he has long since gone silent and disappeared over the horizon.

You could argue Tomas Ericsson is the most ill-suited priest in the history of cinema. He’s played with a peevish, grumpy lack of hope, inspiration or joy, self-loathing seeping from every pore by Gunnar Björnstrand in what might just be his finest hour. Björnstrand, more comfortable with comedy, struggled with this counter-casting (and his cold, which was written into the script), the bottled-up pressure of the role almost shattering his friendship with Bergman. Following a single afternoon in Ericsson’s life, Winter Light charts his complete disillusionment with his faith, his utter failure to provide spiritual comfort to parishioners and his mix of dependence, indifference and contempt for schoolteacher and some-time lover Märta (Ingrid Thulin), herself a needy, unhappy woman content to play second-fiddle to Tomas’ deceased wife.

Tomas’ faith in God has long since vanished. Winter Light is his own Gethsemane, a parade of painful events and conversations where he waits desperately for some sort of sign or word from the Almighty and is left instead wondering, like Christ, why God has forsaken him. Tomas has become bitter, self-obsessed and self-loathing, going through the motions with a dwindling congregation and unable to muster even the faintest bit of belief in the words that pass his lips.

Winter Light follows up ideas of Through a Glass Darkly (Tomas even talks of a “Spider God”, a destructive force at the centre of a world made of pain). There is an echo throughout of the idea that, if God is love, then letting love into your life (or acknowledging the existence of Love in the world) is proof enough that there is a God, even if he is now silent. If so, Tomas’ rejection of any form of love goes hand-in-hand with his rejection of faith. If he felt love, it was for his late wife – and her death matches the decease of his faith in God. Now he angrily slaps away offers of affection with the same contempt he addresses towards questions of faith.

That offer of love comes from Märta, a mousey teacher trapped under an unflattering hat, the bags under her eyes and spinsterish clothes. She’s played in a performance of sustained, emotive brilliance by Ingrid Thulin. Märta captures her feelings for Tomas – right down to her acknowledgement that she knows he does not love her – in a sprawling, stream-of-consciousness letter (which Tomas has delayed reading – and when he does, he scrunches it into a frustrated ball).

That letter is conveyed to us in a stunning, almost interrupted, seven-minute take where Bergman focuses the camera on Thulin in close-up who delivers the contents of the letter straight to camera. This is a tour-de-force from Thulin, by terms unblinking, honest, self-denying, pained, resigned, hopeful and frustratingly simpering, a masterclass that marks one of Winter Light’s most striking moments of directorial and actorly technique. Few actors could pull this scene off with the grace and emotional commitment Thulin brings to it – and still leave us understanding why Tomas later, with anger frustration, cruelly tells her he has simply had enough of her all-forgiving love.

There is no place for that sort of saintly, Christ-like, love in Tomas’ life. His focus remains his own self-loathing. When meeting with Jonas (Max von Sydow – even more carved from granite than normal, his fixed stillness contrasted with Björnstrand’s twitchy unease), who has come to Tomas for spiritual reassurance to help overcome suicidal thoughts, Tomas can only complain of his own lack of faith. Tomas fails utterly to offer any solace to Jonas, a further mark of his own failure as both a priest and human. Jonas’ suicidal misery at the dread of oncoming Armageddon in the nuclear age, becomes grist to Tomas’ own misery and our priest in turn feels no shame in turning to Märta immediately for reassurance and comfort.

The only person who seems to have considered the nature of faith is disabled sexton Algot (a marvellous performance by Allan Edwall). Algot reflects that the suffering on the cross was not Christ’s true sacrifice – after all that was over in hours. The real suffering was hearing God’s silence on that cross, of the horror of suddenly thinking your life’s work may have been a waste of time, that he evangelised for someone silent or indifferent or worse. It would tie in directly with Tomas’ own doubts – except it’s pretty certain Tomas isn’t listening to him.

Maybe that’s partly the problem. We don’t listen to God, because we no longer expect him to talk. At one point, Tomas asks why God has fallen silent while behind him light suddenly pours through the Church window. Is that a sign of a sort? If it is Tomas doesn’t look and when he does, he doesn’t think. Instead, he contributes to the silence of God – as the closest thing to his vessel he fails to listen, fails to help and focuses only on his own pain.

Winter Light is a gorgeous film, full of striking light and shade by cinematographer Sven Nykvist. It’s also a bleak, grim, hopeless film, the best hope it can offer being God might have been real but he’s long since turned his back on us, just as we’ve turned out back on him. It’s magnified when we reject the thing he might have left for us, love itself. Winter Light is intensely thought-provoking, but rivetingly intelligent in the way the best of Bergman is. Björnstrand is superb and Thulin is extraordinary, in a film that carries worlds of meanings in its spare 80 minute runtime.