Distanced and measured film that becomes a heartbreaking study of lonely obsession and destruction addiction

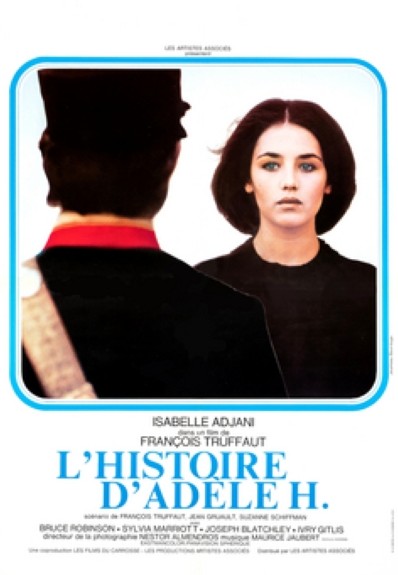

Director: François Truffaut

Cast: Isabelle Adjani (Adèle Hugo), Bruce Robinson (Lieutenant Albert Pinson), Sylvia Marriott (Mrs. Saunders), Joseph Blatchley (Mr. Whistler), Ivry Gitlis (The hypnotist), Cecil de Sausmarez (Mr. Lenoir), Ruben Dorey (Mr. Saunders), Clive Gillingham (Keaton), Roger Martin (Dr. Murdock)

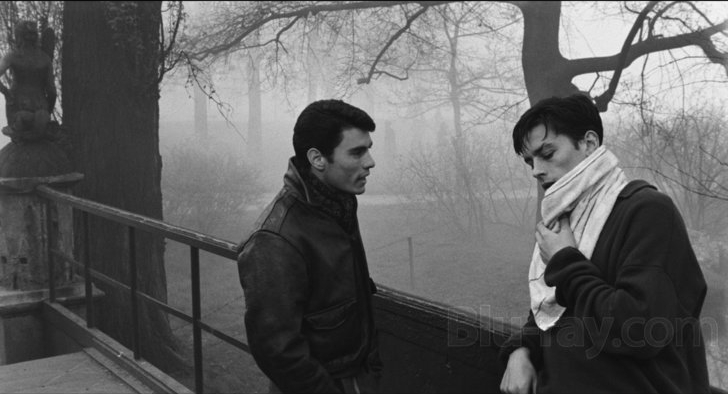

In 1863 there was, perhaps, no man more renowned in France than Victor Hugo. Which made it almost impossible to fly under the radar if you were his daughter. But that’s what Adèle Hugo (Isabelle Adjani) wants in Halifax, Nova Scotia, under the name Adèle Lewly. She’s there in pursuit of British army officer Albert Pinson (Bruce Robinson). Adèle loves Pinson truly, madly, deeply – and obsessively, believing he has promised marriage and ignoring his clear lack-of-interest. Adèle is willing to go to almost any lengths, spin any desperate story, burn through any amount of money, debase herself to a desperate degree to marry Pinson, as her own mental health collapses.

Based on Adèle’s own diaries (written in a code deciphered after her death), The Story of Adèle H unpeels the layers of a destructive obsession that has a terrible emotional impact on all involved. Truffaut’s film can seem cold and precise, as chilly at points as its Halifax settings (in fact shot in Guernsey, historically Hugo’s residence at this time after his banishment from France), his camera keeping an unobtrusive distance and slowly, carefully following the increasingly frantic actions of its lead.

But it’s part of Truffaut’s intriguing dance with our sympathies and loyalties. A more high-falutin’ personal drama may well have tipped us more strongly in our feelings about the desperate Adèle or the controlled Pinson. Instead, Truffaut’s film encourages us to see the story from both perspective and unearths a sort of as well as a tragedy in Adèle’s obsessive quest. But it also demonstrates Pinson’s unpleasant coolness and self-obsession, while allowing us to see his life is being destroyed by a stalker.

Of course, part of us is always going to be desperate for Adèle to shed her feelings for Pinson, who feels barely worth the obsessive, possessive desire she feels for him. A lot of that is due to Isabelle Adjani’s extraordinary performance. A young actor (over ten years younger than Adèle), she not only makes clear Adèle’s intelligence (this is a woman who composed music and wrote and red copiously) and her charm, but also her fragility and desperation. Adjani makes Adèle surprisingly assured and certain throughout, independent minded and determined – it’s just that her feelings are focused on a possessive, all-consuming obsession that is undented by reality.

It says a great deal for the magnetic skill Adjani plays this role with, is that we can both be frustrated and even disturbed by her actions but still see her relentless pursuit as (in a strange way) oddly pure. Truffaut twice quotes Adèle writing about the power of a love that will see someone crossing oceans to follow their beloved, and there is a daring bravery to it, a commitment to being herself and following her desires in a world that is still set up to favour of man over woman. It’s also easy to feel sympathy for her at Adjani’s tortured guilt about the drowning of her sister (vivid nightmares of this haunt her) just as the searing pain Adjani is able to bring to the role is deeply emotional.

But that doesn’t change the unsettling awareness we have of the possessive horror of her actions. Adjani’s Adèle is an addict, the shrine in her room she builds to Pinson just part of the self-destructive behaviour of a woman who lies to everyone about her relationship with Pinson and pours every penny of her income into her next hit of trying to win him. Like a stalker she moves from following Pinson around to the streets to ever more extreme actions: spying on Pinson with his new lovers, hiring a prostitute to sleep with him (as both a perverse gift and a bizarre way to control his sexuality), tell his fiancée’s family she’s a jilted pregnant wife, haunt Pinson on a hunt clutching a waft of notes as a bribe while carrying a cushion stuffed up her dress… Her actions become increasingly more and more unhinged – so much so her attempt to recruit a fraudulent mesmerist to hypnotise Pinson into marriage starts to feel like the most sane and reasonable of her plans.

And slowly we realise that Adèle, for all our first feelings towards her are sympathy, is destroying herself just like an addict jabbing another needle into their arm to try and capture her next hit. Her obsession starts to destroy her health, reducing her to a dead-eyed figure walking the streets in an ever-more crumbling dress, refusing to move on, reducing herself to penury but still following Pinson like a ghost. She alienates herself from people, lies to her family, steals money… it’s a spiral of a junkie.

We can wonder what she sees in Pinson – but, like all addictions, that’s hardly the point. It’s almost the point that Robinson’s Pinson is a bland pretty boy. (It’s quite telling that he’s so forgettable, than on arrival in Halifax Adèle even mistakes a random officer – played by Truffaut – as Pinson). Our first impression of him is as a coldly ambitious, selfish fellow, a rake on the chance. And maybe, to a degree, he is. But it’s hard to take Adèle as a fair witness for whatever claims she makes about the promises Pinson makes. And the longer it goes on, the more its hard not to feel for the destructive effect Adèle’s constant presence has on Pinson. It costs him a marriage, his status and nearly his career. Does he really deserve this for being, really, just a rather selfish guy?

The Story of Adèle H takes our perceptions and makes clear how our feelings can shift and become more complex. Because really Adèle’s problem is not that she has been jilted: but that she is clearly not well, her mental health collapsing in front of her eyes as solitude and secrecy feed her lonely obsession. Her obsession is so great that she can acknowledge she both loves and despises Pinson, but not let that dent her unrelenting , irrational determination to marry him. This destroys her life.

In fact, it becomes hard not to feel sympathy for both characters whose lives are scarred by unrelenting self-destruction. And Truffaut’s approach in his filming actually adds a great deal to this, its forensic distance on this terrible affair placing it under a microscope that reveals clearly the nightmare they are both trapped in. Match that with Adjani’s incredible performance, a star-making turn that burns through the celluloid in its intensity, and you’ve got a quiet but subtly moving film that grabs you almost unawares in its emotional force.